FPGA Key Gen

Disclosure of Funding Source:

This research was conducted at the Georgia Institute of Technology

under the supervision of Dr. Jun Ueda, completing in January 2024,

resulting in the following publication: Encrypted Sensor and Actuator Interface for Encrypted Control Signals via Embedded FPGA Key Generation.

This study was supported in part by National Science Foundation Grant Nos. 2112793.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do

not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Research Goal

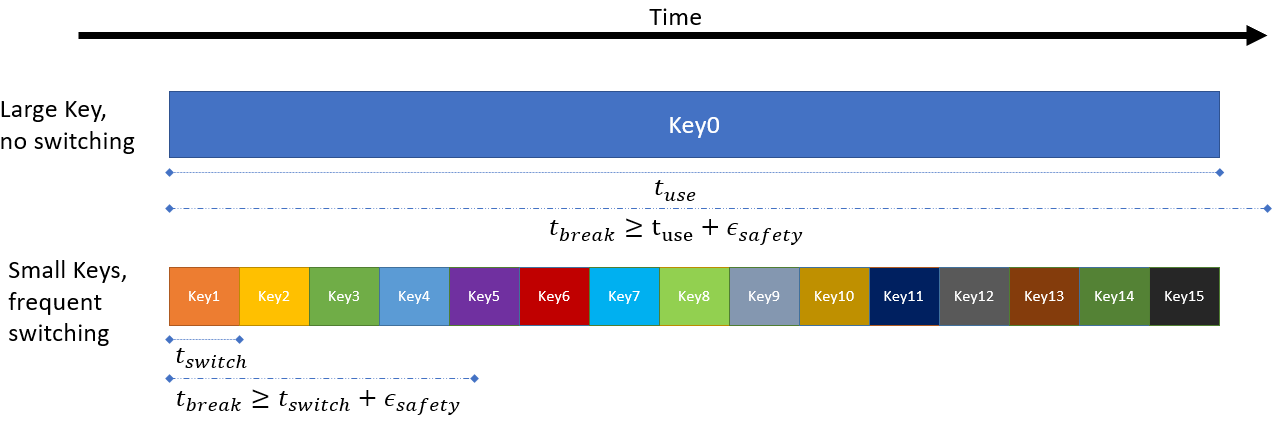

Homomorphic ciphers are instantiated with a set of security parameters. Beyond security these parameters also affect the performance of an encrypted calculation, with stronger parameters resulting in slower computations. This presents a design challenge for encrypted controllers as a designer must balance security against controller refresh speed.

A high refresh rate is a must for a controller to operate, thus an encrypted control system tends to prefer small keys to allow fast encrypted calculations. However, small keys are more vulnerable to cryptographic attack as compared to large keys.

This research proposes a solution to the above problem. If we can periodically switch the small key, at a rate faster than any attacker could break the current small key, then the system would gain cryptographic security comparable to a large key.

System Design

One of the challenges of using this many-small-key approach is that generating cryptographic keys is itself a burdensome computation.

To overcome the computational burden the research produced an FPGA based design with the following architecture.

First, each sensor/actuator in the system has an Enc/Dec circuit attached directly to its output/input, reducing the time the signal spends unencrypted to increase security.

Additionally there is a KeyGen circuit which periodically generates new keys and broadcast the keys to the Enc/Dec circuits, who then update themselves with the new key.

This design is depicted in the figure below:

Enc circuit into the sensor node, the system can conceal the sensor signal from the cloud. The embedded Dec circuit in the actuator node then retrieves the control signal calculated by the cloud. The KeyGen circuit creates a new active key periodically replacing the key used by the other circuits.

The encrypted signal is sent to the encrypted controller as input, which produces an encrypted output per a typical encrypted controller setup.

Random Number Generator

The exact key implementation details will depend on the cipher chosen, since this research considered an integer based cipher prime generation will be the primary problem to overcome. Finding prime numbers is a challenging problem, and is indeed how many ciphers gain their strength, so we should expect a nontrivial computational burden when constructing a prime generation circuit.

This research uses the well known Miller-Rabin primality test (MR) to find primes. Using the MR test we can decided if a random number is prime or composite, but this alone will not find a prime for us, just tell us if a candidate is prime. So to complete the prime generation module we need an random number generator (RNG) circuit.

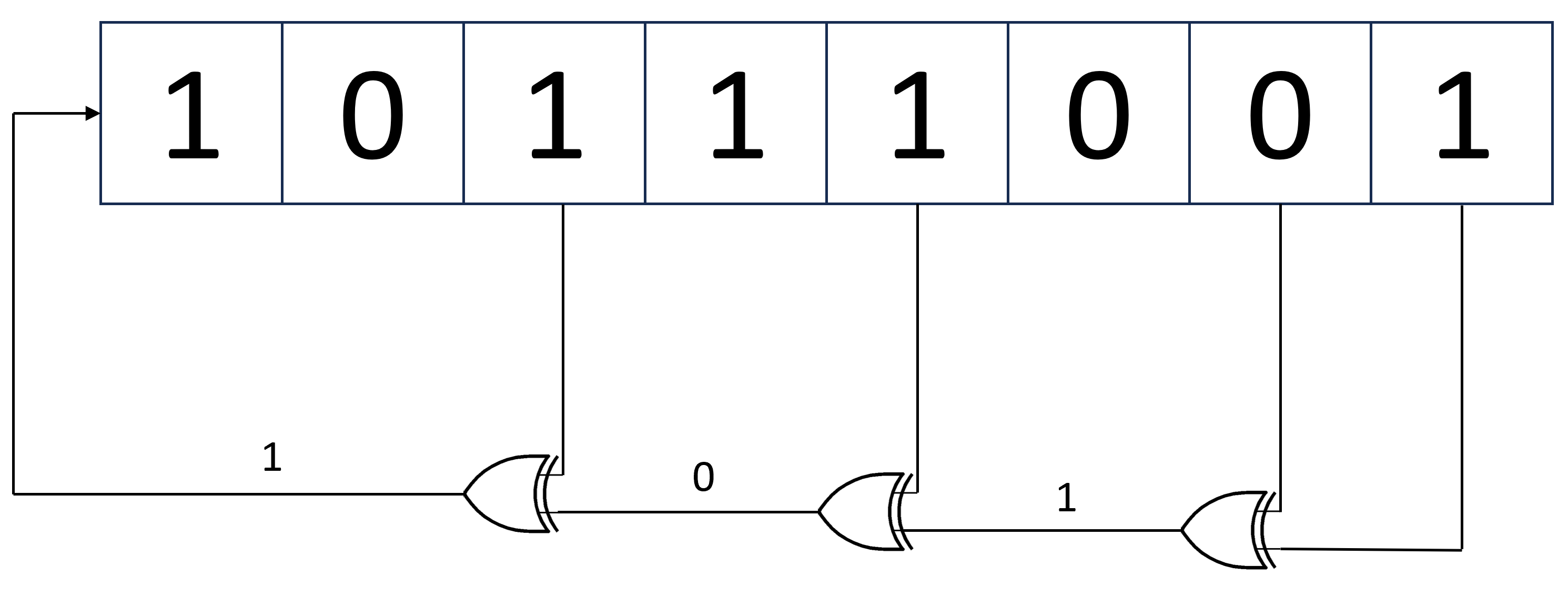

While true randomness is not achievable within deterministic devices such as Field Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs), pseudorandom number generators can be implemented utilizing a starting seed to produce random numbers. One such example is the Linear Feedback Shift Register (LFSR) depicted below:

XORing together the tapped bits we can create a highly random sequence of register values. Note a new bit is feed back into the shift register every clock cycle.

An LFSR consists of a clocked shift register with feedback from its constituent bits, often referred to as “taps”, as depicted above. By applying the exclusive or (XOR) operation between bits within the shift register, a new pseudorandom bit value can be introduced into the register at every clock cycle.

Primality Test

TODO: FIX THIS SECTION.

The Miller-Rabin primality test is a probabilistic primality test based on Fermat’s Little Theorem. It “checks” the primality of a number \(n\) by attempting to prove it to be composite. So its less of a primality test and more of a composite test. Still, be successively checking the same prime repeatedly we can gain high confidence that it is in fact a true prime.

Fermat’s Little Theorem can be manipulated to come to the following form:

\[ a^{p-1} \equiv 1 \mod p \]

Where $p$ is some prime and $a$ is any natural number. While the above is a necessary condition (it holds for all primes) it is not a sufficient condition for finding primes i.e. there are some composite numbers that will satisfy Fermat’s little Theorem.

The Miller-Rabin primality test works by taking the inverse of Fermat’s Little Theorem to create a composite test. Thus we can say that $a$ is a witness to $n$ being composite if:

\[ a^{n-1} \not\equiv 1 \mod n \]

However, even if $n$ passes the above test, there is a chance that it is a strong pseudoprime, for which the corresponding value of $a$ would be a strong liar. To remedy this, the Miller-Rabin test is performed several times on a potential prime, reducing the chances that it is a strong pseudoprime with so many strong liars. This gives the following probability:

\[ P(\text{$n$ is prime after $k$ checks}) \approx 1 - \left( \frac{1}{4} \right)^k. \]

Thus we can use this repeated running of Miller-Rabin to achieve arbitrarily high confidence that a number is prime.

Experimental Setup

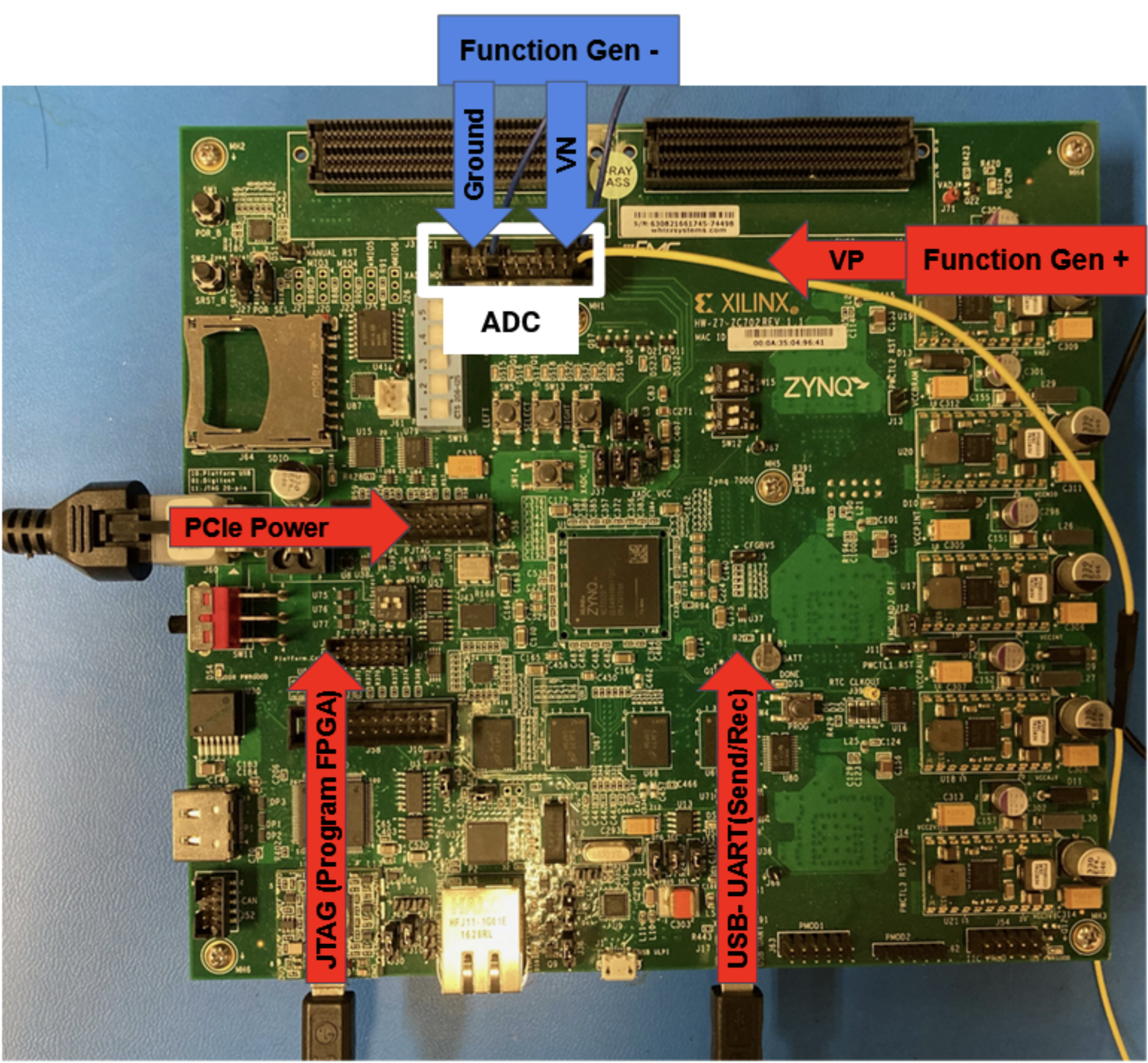

To emulate a sensor signal in a consistent and reliable way a $\sin$ wave was produced by a function generator and fed into an analog to digital converter (ADC). The ADC signal was than fed through the internal encrypt logic implemented on the FPGA. This simple setup can be seen below:

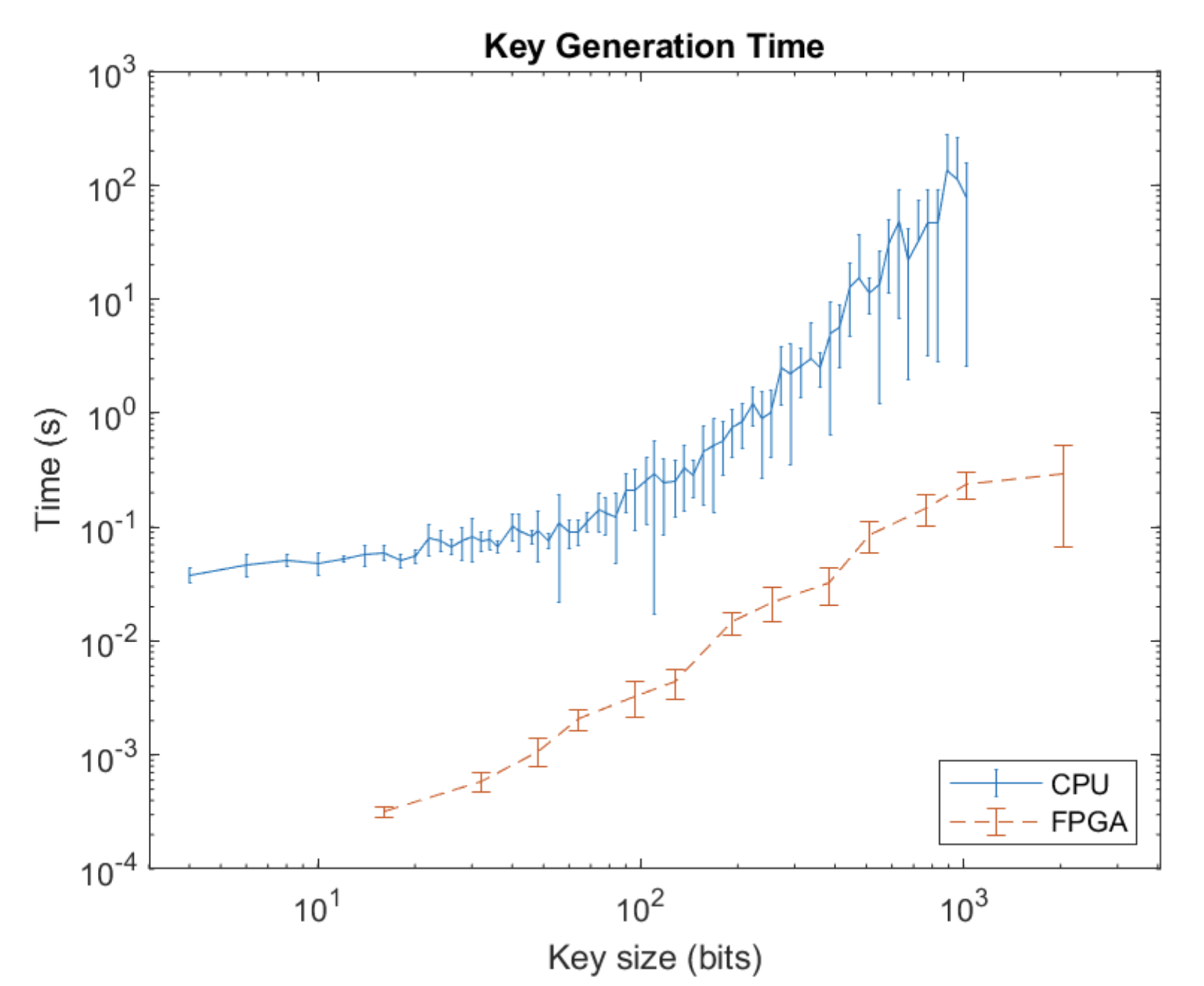

Additionally we looked at the performance of generating increasingly larger keys on a CPU vs using our FPGA design. These results are captured in the plot below: Note that the CPU implementation appears to be growing exponentially while the FPGA plot shows a linear trend. This is because a CPU is limited by the size of its registers and processor word size while an FPGA does not have the same limitations and can simply allocate more gates to compensate for the increased computational burden.

While the FPGA shows amazing results with its linear performance it should be noted that the increased gate usage for large key generation comes with significant increases in power consumption. Thus an FPGA based cryptographic key generation system is limited by power consumption as compared to computation time.

Conclusion

This research set out to address the issue of security vs refresh rate posed by cipher key size (recall a small key is insecure but allows for fast encrypted calculations). A novel key switching procedure was proposed where small keys are constantly switched between to allow for fast calculation and secure calculations as the keys are generated faster then they can be hacked. An FPGA based support circuit was successfully constructed to generate the cipher keys and broadcast them to relevant encryption and decryption circuits at an acceptable rate for real-time application.